The notion that ancient island settlers were maritime novices is being upended by fresh archaeological findings. A new analysis of stone tools from Southeast Asia is rewriting the script on early human seafaring, suggesting that open-ocean travel may have been mastered far earlier than previously believed.

For decades, scholars assumed that the seafaring skills required for such voyages were beyond the capabilities of Paleolithic communities. However, new research published in the Journal of Archaeological Science challenges that assumption, arguing that innovation during this period was not confined to Africa and Europe. The breakthrough comes from stone artifacts recovered in the Philippines, Indonesia, and Timor-Leste, which point to maritime knowledge comparable to that of much later societies and may date back as far as 40,000 years.

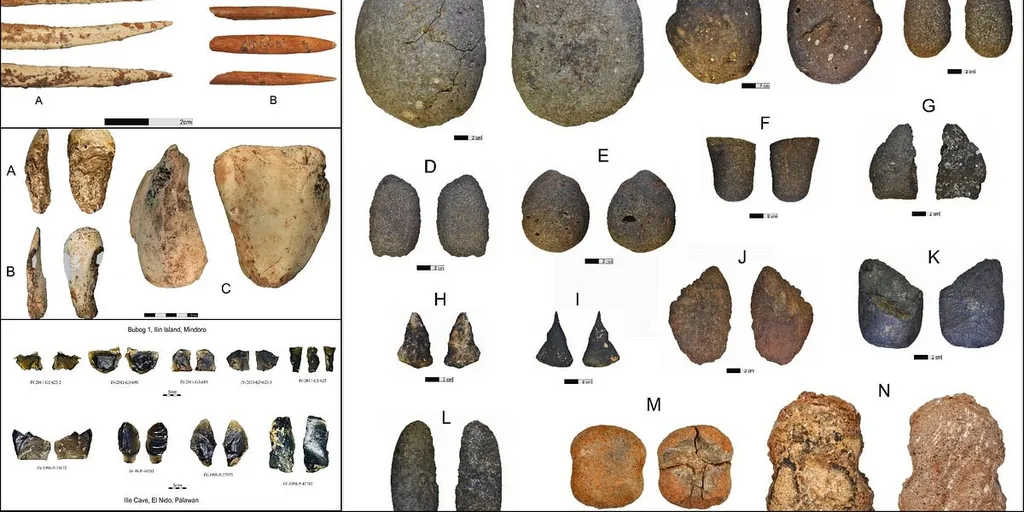

The main challenge in confirming such early nautical activity has been the scarcity of surviving organic materials, such as wood or fibers, which would have formed ancient boats. However, the study argues that recently identified stone tools provide indirect evidence of these missing organic components. Researchers found signs of plant processing linked to the “extraction of fibers necessary for making ropes, nets, and bindings essential for boatbuilding and open-sea fishing.” These findings sit alongside fishing hooks, net weights, gorges, and the remains of deep-ocean species including tuna and sharks.

“The remains of large predatory pelagic fish at these sites indicate the capacity for advanced seafaring and knowledge of the seasonality and migration routes of those fish species,” the research team wrote. The collection of tools and marine remains “indicates the need for strong and well-crafted cordage for ropes and fishing lines to catch the marine fauna.” The authors suggest that the tools illustrate complex rope-making and fishing practices, implying that early mariners used plant fibers to build and secure their vessels before adapting similar materials for ocean-going hunts.

Discoveries of fossils and tools on isolated islands have long been interpreted as signs that early modern humans drifted across oceans by chance. The new study challenges this, arguing that these crossings required deliberate planning rather than accidental journeys. Instead of unintentional voyages on makeshift rafts, the researchers propose that prehistoric travelers were informed navigators equipped with the skills needed to cross deep waters.

In a university press release, the researchers added that the presence of sophisticated maritime technology in prehistoric Island Southeast Asia highlights the ingenuity of “early Philippine peoples and their neighbors,” whose knowledge “likely made the region a hub for technological innovations tens of thousands of years ago and laid the groundwork for the maritime traditions that still flourish in the region today.”

This research not only reshapes our understanding of early human capabilities but also underscores the complexity and resourcefulness of ancient societies. It prompts a reevaluation of the technological and cognitive advancements of our ancestors, suggesting that the mastery of the seas may have been a more widespread and earlier achievement than previously thought. As we continue to uncover the maritime past, the story of human ingenuity and adaptation becomes ever more fascinating.