In the abyss of the Pacific Ocean, a tiny coral has made a home on mineral-rich rocks that are the target of a burgeoning deep-seabed mining industry. The discovery of Deltocyathus zoemetallicus, a new species of deep-sea coral, has sparked urgent questions about the potential impact of mining on this fragile ecosystem.

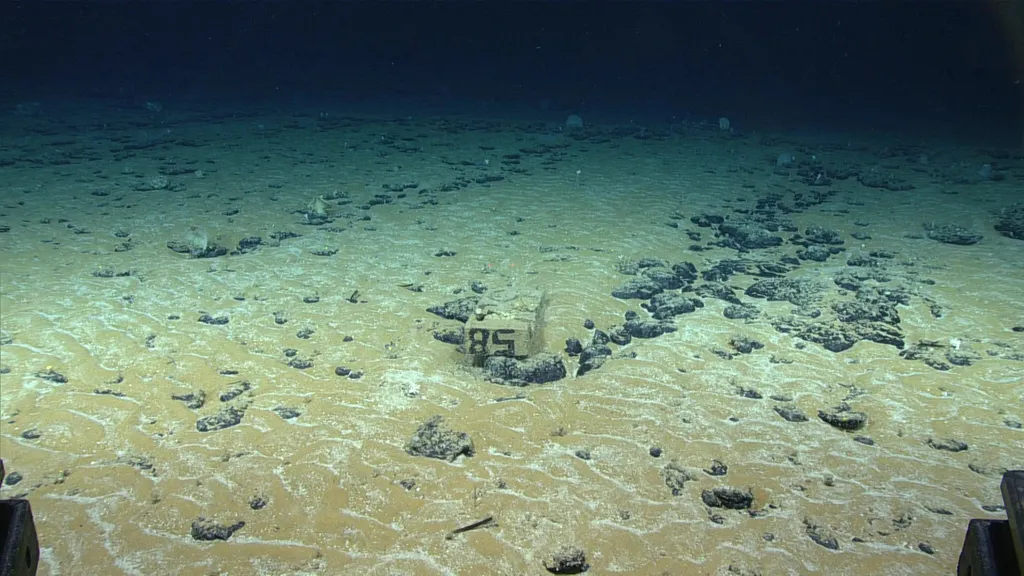

The coral, found more than 4,000 meters below the surface in the Clarion–Clipperton Zone (CCZ), is the first known hard-coral species to live directly on polymetallic nodules. These potato-sized lumps, rich in manganese, nickel, cobalt, and other critical metals, are the focus of growing international interest for their role in electric vehicle batteries and renewable energy technologies.

However, the nodules grow extremely slowly—only a few millimeters over thousands of years. If mining were to remove them, this newly discovered species could lose its only known habitat—potentially before we fully understand its biology or ecological role.

“This tiny coral is a hidden gem of the abyss,” says Dr. Nadia Santodomingo, Head of Marine Invertebrates I Section at the Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum Frankfurt. “It lives directly on the nodules that mining companies are preparing to extract. If these nodules are removed, we risk wiping out an entire species we have only just found.”

The discovery was made by an international research team led by Dr. Guadalupe Bribiesca-Contreras from the National Oceanography Centre (NOC) and Dr. Santodomingo. The study, published in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, highlights the urgent need for further research and careful consideration of the environmental impact of deep-seabed mining.

Unlike shallow-water corals that often host symbiotic algae, Deltocyathus zoemetallicus survives in total darkness. This species is an azooxanthellate scleractinian, meaning it lacks an algal partner to provide nutrients, instead feeding on particles that drift through the water.

Using box corers during expeditions onboard the OSV Maersk Launcher and the RRS James Cook, scientists carefully collected the new coral specimens and their nodule homes. The team then analyzed the animals using high-resolution imaging and 3D micro-CT scanning to confirm that it represents a species new to science.

Corals of the genus Deltocyathus are found in every ocean basin except the Arctic and around Antarctica. They typically inhabit depths between 200 and 1,000 meters, with the deepest known species recorded at 5,080 meters. Most Deltocyathus species are free-living, meaning they sit lightly atop the seafloor sediments, with the exception of the Atlantic species Deltocyathus halianthus and now Deltocyathus zoemetallicus, which attach to hard substrates.

“This discovery underscores how little we know about life in the deep sea,” says Dr. Guadalupe Bribiesca-Contreras, lead author and Applied Scientist at NOC. “Every new species we find reminds us that the ocean floor is a living ecosystem and we still have so much research to do to explore and understand it fully.”

The deep ocean floor, once thought to be flat, muddy, and largely lifeless, hosts a wide range of habitats and rich biodiversity. The CCZ holds the world’s largest known deposits of polymetallic nodules, making it a prime target for mining. However, the discovery of Deltocyathus zoemetallicus serves as a stark reminder of the potential consequences of disturbing these delicate ecosystems.

As the world races to secure critical metals for the transition to renewable energy, the balance between technological advancement and environmental conservation becomes increasingly precarious. The discovery of this new coral species underscores the urgent need for further research and careful consideration of the environmental impact of deep-seabed mining. The race is on to understand these hidden gems of the abyss before they are lost forever.