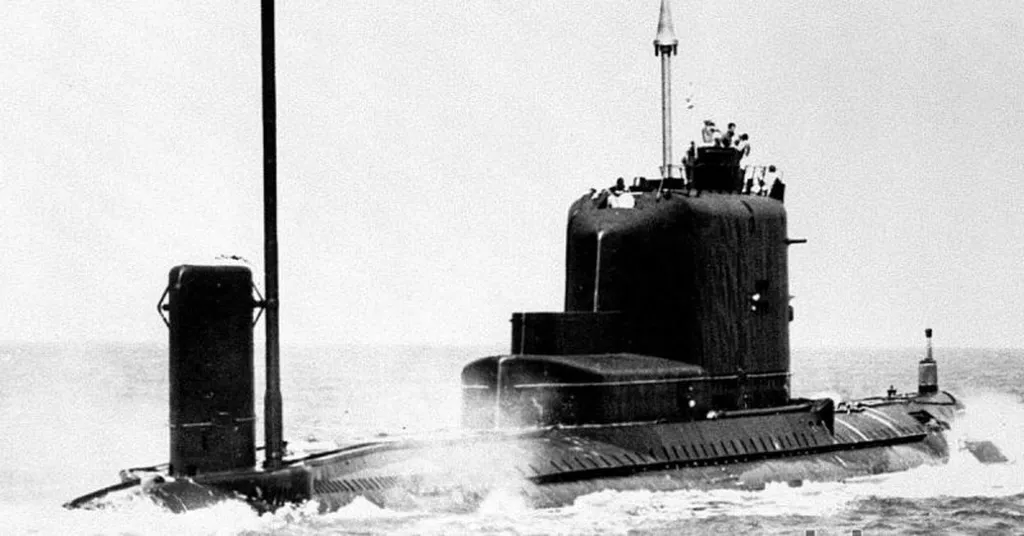

In the annals of Cold War espionage, few projects rival the audacity and ingenuity of Azorian, a top-secret mission to recover a sunken Soviet submarine from the depths of the Pacific Ocean. The story begins in March 1968 when the U.S. Navy detected an extensive Soviet naval and air search in the North Pacific. Over the following months, the U.S. concluded that the Russians had lost a submarine and were unable to locate it. Using acoustic data from Pacific listening stations, the Navy pinpointed an explosive event in the same area where the Soviets were searching. This led to the discovery of the wreckage of the Soviet submarine K-129, a diesel-electric Golf II-class vessel armed with nuclear-tipped ballistic missiles.

The K-129 lay at a staggering depth of sixteen thousand feet, presenting an extraordinary challenge. The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) took on the task, devising a plan to recover the submarine without alerting the Soviets. The project, code-named Azorian, was nothing short of audacious. The CIA’s Science and Technology Directorate, known for developing intelligence satellites and the U-2 spy plane, proposed using a giant surface ship to lower a three-mile-long pipe string with a claw-like capture vehicle to retrieve the submarine.

To conceal the true purpose of Azorian, the CIA crafted an elaborate cover story: the project was a commercial venture to mine manganese nodules from the deep seabed. Howard Hughes’ Hughes Tool Company in Houston, Texas, served as the front, providing the necessary financial and operational cover. The ship built for this mission, the Hughes Glomar Explorer, was an engineering marvel. Designed by John Graham of Global Marine, the Explorer displaced over fifty thousand tons and featured a derrick taller than a twenty-four-story building. The ship’s moon pool, where the capture vehicle would be lowered and raised, was a monumental feat of engineering.

The capture vehicle, built by Lockheed and nicknamed Clementine, was a sophisticated piece of technology. It used acoustic sensors, closed-circuit TV cameras, and thrusters to position itself over the submarine wreckage. Hydraulic cylinders and davits were designed to lift the submarine from the seabed, though the mission faced a significant setback when part of the K-129 broke away and sank back to the ocean floor.

The Hughes Glomar Explorer arrived at the wreck site on July 4, 1974. Bad weather delayed the operation until mid-July, when the capture vehicle was lowered to a depth of sixteen thousand two hundred feet. Despite encountering unexpected resistance, the davits successfully cradled the submarine. However, during the recovery process, a significant portion of the K-129 broke away and was lost, sinking back to the seabed.

The mission, though partially successful, demonstrated the extraordinary lengths to which the U.S. would go to gain intelligence during the Cold War. The Hughes Glomar Explorer and the capture vehicle remain testaments to the ingenuity and determination of the teams involved. The story of Azorian is a reminder of the high-stakes espionage and technological innovation that defined an era.